Short and Sweet:

“The Last Laugh” is the story of a personal tragedy: an aging hotel doorman loses his identity and prestige along with his uniform and is subsequently mercilessly humiliated by society.

Murnau’s film, which largely does without intertitles, is considered a milestone in film history and a highlight of German silent cinema.

Action

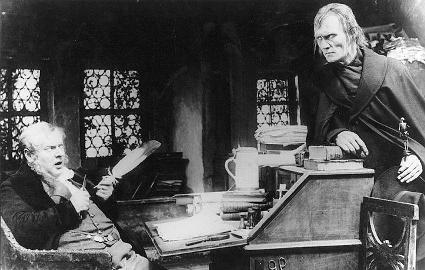

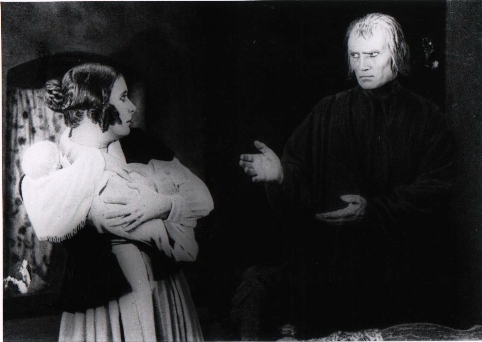

When the doorman of the “Atlantic” hotel (Emil Jannings) walks home in his smart uniform, he is respectfully greeted by neighbors in the backyard. But when the hotel manager (Hans Unterkircher) observes the doorman struggling after carrying a suitcase and resting for a few minutes, he appoints a younger man as the doorman and intends to send the old man to a retirement home. In desperation, the doorman tries to prove his strength by lifting a heavy suitcase in the manager’s office, but he collapses. A bellboy yanks off the doorman’s uniform, and a staff member shows him his new workplace in the restroom.On that very day, his niece (Maly Delschaft) is getting married. He can’t go home without his uniform! Late at night, he sneaks into the hotel manager’s office and steals the uniform, which brings him recognition and self-worth at the wedding. Once again, he symbolizes luxury and the wider world. That night, he is tormented by nightmares. The next morning, he has almost forgotten what happened. When he perceives the submissive expression of a neighbor as a grimace, he attributes it to having drunk too much. It is only when he sees the new doorman standing in front of the “Atlantic” that everything comes rushing back. Before entering the hotel, he takes off his uniform and checks it into the luggage storage.That day, a relative (Emilie Kurz) plans to surprise him with a freshly cooked lunch, which she brings to the hotel in a dish. But there stands a strange doorman in front of the hotel! They tell her that the one she is looking for is now a restroom attendant. She cannot believe it. A bellboy fetches the former doorman from the restroom. When the woman sees that it’s true, she runs home in horror. There, she excitedly tells the newlyweds. A neighbor who has been eavesdropping at the door spreads the news. It doesn’t help that the restroom attendant puts on the uniform again on his way home: the neighbors mock and laugh at him. He flees back to the hotel.With the help of the night watchman (Georg John), he returns the stolen uniform and then goes back to his place in the restroom.A title card reads that the story is now actually over. “But the author takes it upon himself to give the abandoned one a sequel, where things proceed somewhat like they unfortunately do not in real life.”The newspapers report that the Mexican multimillionaire Money died in the restroom of the “Atlantic” hotel. According to his will, the one in whose arms he died inherits him. Thus, the former doorman and restroom attendant now circulates as a wealthy guest at the “Atlantic,” even inviting the night watchman to dinner, who still jumps up at the sight of the manager. In front of the revolving door of the hotel, a four-horse carriage waits for the nouveau riche. Generously, he invites a beggar into the carriage. The beggar sits across from him and slips to the floor since there is no bench.

About

Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau directs the story so compellingly that he manages without intertitles, the only exception being the announcement of the sequel. The narrative is told almost exclusively from the protagonist’s perspective. Extreme angles, shadow effects, and theatrical movements are characteristic of Expressionism. What is completely new are the multiple exposures and especially the “unleashed camera,” which zooms, pans, and circles. This experimental approach is not for its own sake but is used to explore and dramatize the psychological development. “A true light play, a true movement play,” stated the “Berliner Börsen-Courier” on December 24, 1924. – “The Last Man” is a milestone in film history and is considered a highlight of German silent cinema.

“The Last Man” was filmed from May to September 1924 in the Ufa studios in Berlin-Tempelhof and on the Ufa lot in Neubabelsberg. The sets were designed by Robert Herlth and Walter Röhrig. The producer was Erich Pommer. The world premiere took place on December 23, 1924, at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo in Berlin.

Three different negatives of the film were produced in 1924: one for Germany, one for the USA, and the third for general export.

Music

New music by Wilfried Kaets for concert organ, MIDI vibraphone, and percussion.

An alternative performance is available for piano and percussion.

The music is structurally oriented toward the film music dramaturgical approaches of the silent film era and partially incorporates themes from film archives of the 1920s, but it is largely a new composition.

This is true in terms of formal aspects, such as the timbres of the MIDI vibraphone, as well as in the actual notation, which presents contemporary composers and does not attempt to replicate old models. This creates an exciting balance of “old images” and “new sounds” that do not simply run contrapuntally alongside or against the film but instead create a dramaturgically coherent interplay.

The silent film has so far been successfully performed in various cinemas, churches, and concert halls in Germany, Luxembourg, and Switzerland. Further concerts are planned.