Live Recording by Wilfried Kaets

Short and Sweet:

The expressionist German silent film classic is presented in a historically unique copy at its original reduced silent film speed on the big screen!

Lively, intense, over-the-top, and expressionistic, the film tells the story of a cashier who wants to spend the first and last day of his ‘free’ life joyfully and carefree with an Italian lady. To achieve this, he steals 60,000 marks from the till and flees into the wild life of the big city, where he is torn between his obsessions.

In the year of its creation, 1920, German cinema owners refused to show the film, and it was even banned in Japan!

A lady wants to withdraw money from her account to pay for a painting, but doesn’t get anything from the director because her account may not be covered.

The cashier is very taken with the lady and literally lusts after her. In his mind, he compares the sophisticated appearance of the stranger with his own petty bourgeois family. The cashier then fills his own pockets with money and makes his way to the lady to help her out with the money.

In the meantime, the painting, a female nude, has arrived. The cashier sees the painting, which stimulates his imagination to such an extent that the lady seems to transform into the naked woman in the painting before his eyes. He desires her. She laughs at him. She no longer needs his money. Presumably the painting has been paid for by her lover after all.

In the meantime, the cashier’s disappearance and the missing money in the bank have been noticed. The cashier goes home. However, the family idyll seems to disgust him. His daughter’s face suddenly appears to him as a skull. He leaves the house in a hurry and runs through the snowstorm of the night into the big city to enjoy his wealth. His boss, the bank manager and the police give chase and narrowly miss him. The family is horrified when they hear what has happened.

In the city, the cashier buys himself a new tailcoat and treats himself to a shave. All dolled up, he attends a bicycle race and bets money, goes to a bar, drinks cocktails and has fun with a woman in the séparée. His next stop is a dodgy basement dive where they play with marked cards and the cashier joins in and wins at first. The Salvation Army passes by the window and a girl takes him out of the dive.

In the Salvation Army tent, like many others, he confesses his story – almost as if in a fever. So he reaches into his pockets and throws the stolen money into the crowd, which people eagerly pounce on. Then the Salvation Army girl’s face also turns into a skull. The cashier looks distraught, the girl is frightened and calls the police. When the police arrive, the cashier shoots himself.

It’s just before midnight

The Film as a critic (by André Stratmann)

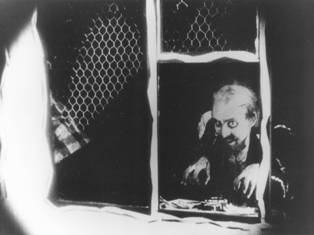

The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari emerged from the years 1919/20 and is one of the few truly expressionistic German films. In Caligari, the alienated, distorted buildings represented an outward manifestation of the human soul, embodying madness. From Morning to Midnight takes this even further. The backdrop against which the actors perform is merely sketched out. It consists of large black areas with white distorted patterns and slanting lines, resembling a house, stairs, arches, etc., as if painted by a child. These patterns are not only continued on the sparse interior (sofa, table, stove, etc.) but also on the actors’ costumes. They often seem to be just a part of the set. Even the makeup of the tragic hero of the story follows this style: a chalk-white face, eyes outlined in black, and an unshaved appearance. The film clearly stands in the tradition of the stage acting experiments of its time.

From Morning to Midnight contains social criticism. It addresses, among other things, the question of wealth and poverty. The corpulent man at the beginning of the film, who deposits a lot of money, moves with difficulty. He is a caricature of the well-fed capitalist, the war profiteer from the recent World War I. In stark contrast, the homeless beggar, who appears repeatedly, represents poverty and misery. The only measure for the fat man, who surrounds himself with a page, is money. He is so high in rank that he is even served personally by the bank manager.

For the poor cashier, sudden wealth means the possibility of escaping from his social constraints (monotonous work, boring family). In his quest for happiness, he throws money around recklessly. However, he earns neither respect nor the hoped-for happiness with women. His attempt to escape fails and ends in a rampage.

The film does not offer the audience the opportunity to identify with the characters. Practically nothing is known about their backgrounds. The actors merely represent specific types (rich man, fashionable woman, prostitute, etc.) and, as mentioned, are sometimes only part of the decoration. It is relatively difficult to follow the plot of the film. Intertitles appear only once, in a single animated title.

The film is based on the expressionist drama of the same name by Georg Kaiser from 1912. It is a so-called “station drama,” which does not follow the classical act structure but consists of a series of individual scenes. The film adaptation is based on this. The play was first performed in the theater in 1917. Karl Heinz Martin, the director of the film, was one of the leading directors of expressionist theater and had previously staged the play with great success on stage.

The film version did not have a premiere. No interested cinema operators could be found. However, From Morning to Midnight must have been shown in some theaters, as contemporary reviews are available. However, the film was heavily criticized, mainly due to the lack of dialogue (or intertitles), which had made the original stage performance so strong. Thus, the “speech and verbal art” with the “rhythm of machine-gun fire” became a strange pantomime in the film. A few years later, Werner Krauss took on the role of the cashier in a radio feature. His biographer Alfred Mühr describes Krauss’s “booming” voice and how he managed to shape the expressionistic style of the piece with it.

Music

While Kaets is generally one of the few specialists in Europe for “historical silent film music practice,” he takes a radically different and highly personal compositional approach here. Instead of relying on research of old film archive collections, cue sheets from film distributors, censorship protocols, or locating historical film music scores, he adopts a contemporary perspective as a film music composer.

He is particularly interested in the “musical tempo” of the film, the film dramaturgy (comparable to the arrangement and weighting of individual movements in a sonata or symphony), and the bizarre atmosphere in terms of narrative structure, decor, and acting direction.

Thus, the music evolves to be as fast-paced, wild, exaggerated, and expressive as the over 80-year-old silent film, which still likely surprises, overwhelms, and perhaps even unsettles many viewers today.

The music attempts to approach this zest for frenzy, madness, experimentation, provocation, mockery, and nonsense.

Register:

Karlheinz Martin (also: Karl Heinz Martin, often abbreviated as K. H. Martin, born: Karl Joseph Gottfried Martin; May 6, 1886, Freiburg im Breisgau – January 13, 1948, Berlin) was a German theater director and, from 1919 to 1939, also a film director and screenwriter.

Karlheinz Martin (also: Karl Heinz Martin, often abbreviated as K. H. Martin, born: Karl Joseph Gottfried Martin; May 6, 1886, Freiburg im Breisgau – January 13, 1948, Berlin) was a German theater director and, from 1919 to 1939, also a film director and screenwriter.