Live recording by Wilfried Kaets

New Music for Solo Organ by Wilfried Kaets, alternative versions for Solo Piano; Organ + Percussion; Piano + Percussion; Piano + Double Percussion

Short and Sweet

Metropolis – The City of the Future

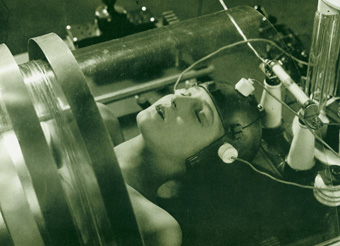

Fritz Lang’s monumental science fiction film combines visual power with a love story about the reconciliation of labor and capital: Above the city, Joh Fredersen rules, while underground the workers toil. Fredersen’s son, Freder, falls in love with the worker leader, Maria.

At the same time, Rotwang, the inventor, creates a steel robot and, on Fredersen’s orders, gives it Maria’s appearance. The false Maria incites the workers, who leave their machines, triggering the city’s flooding. Only through Freder and Maria’s efforts can Metropolis be saved. The city’s rulers and workers come to realize that “brain” and “hands” belong together.

*Metropolis* is a German feature film by Fritz Lang from 1927. It is one of the most famous science fiction films in cinema history and also one of the most visually influential silent films. After its premiere on January 10, 1927, in Berlin, the film was not a commercial success. Even a revised and shortened second version released later that year (premiere on August 25, 1927, in Stuttgart and Munich) did not attract an audience. The film’s historical significance was recognized only in later decades. With production costs of 5 million Reichsmarks (approximately 16.6 million euros in today’s purchasing power), *Metropolis* was the most expensive film in German cinema history at the time. The lack of success temporarily ruined Ufa.

The plot, based on a screenplay by Lang’s wife Thea von Harbou, unfolds across several storylines: Besides the romance between Freder and Maria, there is the romantic-gothic tale of the sorcerer’s apprentice: An inventor creates an artificial human being that brings destruction to all involved. This is contrasted with the intrigue involving the ‘Thin Man’—the eyes and ears of the ruler of Metropolis—and the ultimately thwarted plan to neutralize the hero’s helpers. The second intrigue is Rotwang’s revenge, as he seeks to destroy the son of the man who took his love. Along with elements from folk tales, the film incorporates symbolism of the Virgin Mary and the division into virgin and whore.

Action

Topic and Interpretation

Fritz Lang often and eagerly claimed that during his trip to America in October 1924, while the ship was still before the New York harbor at night, he conceived the story of *Metropolis* upon seeing the skyscrapers and illuminated streets. After his return, Thea von Harbou began work on the screenplay. However, this inspiration could only pertain to the visual ideas realized during filming, not the screenplay itself, which was already near completion by July 1924. Von Harbou also wrote a novel based on the film’s plot.

In depicting the social order, *Metropolis* aligns in part with Marxism; it features two sharply divided classes, with one exploiting the other and no opportunities for upward mobility. The obscurity of some machines represents alienation from labor. On the other hand, the storyline clearly critiques the revolution that destroys the lower class’s livelihood. The promoted cooperation between classes, instead of class struggle, is reminiscent of National Socialism. Such a corporatist economic structure was consistent with the NSDAP’s program.

The Tower of Babel parable is altered: in this version, the planners and workers speak the same language but do not understand each other; there is no divine intervention to destroy the tower. Instead, the tower is simply left unfinished due to the workers’ revolt against their oppressors. The real Maria, who symbolizes goodness and announces the arrival of a savior, is drawn from Christian tradition.

Fritz Lang later admitted that he now considers the idea that the heart mediates between hand and brain to be incorrect and thus no longer likes the film. He viewed the problem as social rather than moral. Although the core thesis of brain, hand, and heart originated with Thea von Harbou, Lang felt he was at least 50 percent responsible since he directed the film. At the time, however, he was more interested in technique and architecture than in the narrative.

The film’s failure with contemporary audiences can also be attributed to its social depiction opposing the then-unquestioned belief in progress, which held that technological innovations would lead to a more humane and civilized society. Science fiction at the time typically presented positive utopias, while Lang’s future featured a return to the slave armies of biblical times. The colossal machines create a more degrading life for the lower class than they had in the pre-industrial era. The masses are easily manipulated through instinctive reflexes, and even medieval rituals like witch burnings are revived. “With increasing industrialization, the machine ceases to be merely a tool, begins to develop a life of its own, imposes its rhythm on the human. The human, moving mechanically as part of the machine, becomes a part of it.”

A future study like *Metropolis* can be compared with the present to show what has diverged from its predictions: the social differentiation in affluent societies, the tertiarization, and the relocation of industry from cities.

The Architecture

*Metropolis* is a city comprised of skyscrapers, with architecture reminiscent of the skyscrapers of the time, particularly those in New York. The design and creation of the buildings for this utopian film city were carried out by film architects Otto Hunte, Erich Kettelhut, Karl Vollbrecht, and Walter Schultze-Mittendorf (responsible for the Maschinenmensch and sculptures).

In the city’s canyons, streets and tracks for monorails wind through. The buildings used by the upper class are lavishly decorated, while the underground workers’ city appears plain and grim. Additionally, there are more medieval-inspired structures, such as the Gothic cathedral and Rotwang’s house, which resembles the director’s residence designed by Otto Bartning (1923–25) in Zeipau. Rotwang’s workshop looks more like a magician’s kitchen than a scientific laboratory.

Background, Aesthetics and Production

The film, directed by Fritz Lang from May 22, 1925, to October 30, 1926, involved a significant investment in technology and actors, emphasizing aesthetic aspects and visual staging. *Metropolis* is meticulously crafted with extensive use of extras, sets, and impressive special effects. The film introduced robots, monorails, and video phones to cinema for the first time. Vehicles moving between skyscrapers were animated using stop-motion techniques. Despite the excellent craftsmanship in filmmaking, the story, based on the screenplay by Thea von Harbou, comes across as relatively melodramatic and naïve.

Working Conditions while Production

Despite all the artistic acclaim, Fritz Lang’s treatment of the actors has faced criticism. For a scene in which Gustav Fröhlich falls to his knees before Brigitte Helm, Lang remained dissatisfied even after numerous takes. This particular scene was rehearsed for two days, leaving Fröhlich barely able to stand afterward. For the flood scene, poorly nourished children were used in the cold autumn of 1925. During the following winter, extras had to stand in an unheated studio hangar in the nude for the repeatedly filmed scenes. The mass scene of the flooded city, which occupies about 10 minutes in the film, took over 6 weeks to shoot, during which Lang repeatedly subjected the extras to the icy water. The extras were primarily unemployed individuals who were cheap and available in large numbers.

Brigitte Helm, who played Maria and the Maschinenmensch, had to wear a heavy, metallic costume and almost collapsed several times. Consequently, only relatively short scenes could be filmed, and Helm had to be refreshed with fans by the film’s crew shortly afterward. The film crew spent 14 to 16 hours a day in the studio under poor conditions, with many falling ill. Under the tyranny of the despised Fritz Lang, the extras and crew fared little better than the Babylonian slaves depicted in the film, who were shown to work hard and suffer for the monumental artwork of their ruler. In total, 27,000 extras were used, with filming taking place over 310 days and 60 nights.

Production

More than 500 kilometers of film were exposed for the shots. Lang’s perfectionism, combined with bad weather, extended the production, which increasingly strained the capacity of Ufa. The company’s management held the producer, Pommer, solely responsible for the debacle and dismissed him on January 22, 1926, even before the film’s completion.

Contemporary reception of critics

*Metropolis* was a commercial failure in 1927. After its premiere on January 10 at the Ufa-Palast am Zoo and the Ufa-Pavillon at Nollendorfplatz, it drew only 15,000 viewers by May 1927. Consequently, Ufa abandoned plans for a nationwide release of the original version, withdrew the film, and released a heavily edited and revised version in the summer. This version premiered on August 25, 1927, at the Sendlinger-Tor-Lichtspielen in Munich and the Ufa-Palast in Stuttgart but also failed to achieve success. The financially struggling Ufa, which had hoped for a breakthrough with *Metropolis*, was acquired by Alfred Hugenberg a few months later.

Criticism following the January 1927 premiere was largely negative. While the film’s visual effects and technical achievements were praised, Thea von Harbou’s screenplay did not receive favorable reviews.

Register

Fritz Lang wurde am 5. Dezember 1890 in Wien geboren und starb am 2. August 1976 in Los Angeles.

Lang studierte zunächst Architektur und Malerei und begann nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, Drehbücher zu schreiben, die von Joe May und Otto Rippert verfilmt wurden. 1919 gab Lang mit dem Film *Halbblut* sein Regiedebüt. Dieser Film leitete eine beeindruckende Karriere ein, in der Lang zahlreiche Filme drehte, die viele als Klassiker der Filmgeschichte betrachten.

In den 1920er Jahren gehörte Lang zu den führenden deutschen Regisseuren. 1933 emigrierte er nach Frankreich und England in die USA, als Joseph Goebbels ihm ein Angebot machte, eine Art “Reichs-Filmintendant” zu werden. In den USA begann Lang eine zweite Karriere und drehte vorwiegend Action-Filme. Sein stilistisches Markenzeichen in den frühen deutschen Filmen war der ornamentale Stil und die architektonische Struktur. Seine Werke zeigten oft riesige Bauten, raffinierte Lichteffekte und drohende Schatten, wobei der Mensch häufig als Opfer schicksalhafter Verstrickungen dargestellt wurde. Die Kamera bannte die Figuren konsequent in ein Labyrinth strenger Linien und stellte sie monumentalen Dekorationen oder der Masse gesichtsloser Menschen gegenüber.

Lang erkannte bereits in den 1920er Jahren die heraufziehenden Probleme seiner Zeit. Obwohl seine Filme oft intuitiv und nicht kritisch reflektierend waren, führte dies gelegentlich zu Missverständnissen darüber, ob Lang sich mit den gesellschaftlichen Zeitströmungen identifizierte, besonders weil seine Frau und langjährige Drehbuchautorin, Thea von Harbou, sich nach 1933 schnell mit den neuen Verhältnissen arrangierte.

In Hollywood drehte Lang vorwiegend Action-Filme und versuchte gegen Ende der 1950er Jahre, im deutschen Kino wieder Fuß zu fassen, was jedoch scheiterte.

**Filmografie (Auswahl):**

– 1919: *Halbblut*

– 1921: *Der müde Tod*

– 1922: *Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler*

– 1924: *Die Nibelungen: Siegfrieds Tod*

– 1924: *Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache*

– 1927: *Metropolis*

– 1928: *Spione*

– 1929: *Frau im Mond*

– 1931: *M*

– 1936: *You Only Live Once*

– 1942: *Hangmen Also Die!*

– 1944: *The Woman in the Window*

– 1953: *The Big Heat*

– 1958: *Der Tiger von Eschnapur*

– 1959: *Das indische Grabmal*